Musings on life choices (and UK housing)

I didn't set out to work with computers. I initially just wanted some tertiary education under my belt as I'd seen up close the dead end drudgery that was so freely and widely available to the less-educated. I wanted none of that.

Back in 1969, as my school career wound down and I was casting around for something interesting to "do" that would both deliver my tertiary level education and also render me less financially dependent1 on my parents, I briefly considered electrical engineering, and life as a student sponsored by what was then called the Central Electricity Generating Board.2 I made the final shortlist of forty applicants, but not the top 12, alas, so at fairly short notice I opted to follow Big Bro's trail into aeronautical engineering instead. (Actually, I opted for production engineering, but the Apprentice Training Officer wasn't having any of that, bless him.)

The world of UK aviation

So it was that, just a couple of months after watching the Apollo 11 lunar landing on a portable TV in the bar of a Mediterranean hotel, I took a somewhat less grandiose "small step for a man" by dipping my tentative not-quite-18-year-old toe into the adult world of (shudder) work on a five-year sponsored aeronautical engineering apprenticeship. I spent my first year (September 1969 through August 1970 — by which time Big Bro had just set off for New Zealand) living in the Astwick Manor apprentice hostel, gradually learning to get along with the other 30 or so lads (no lasses, alas).

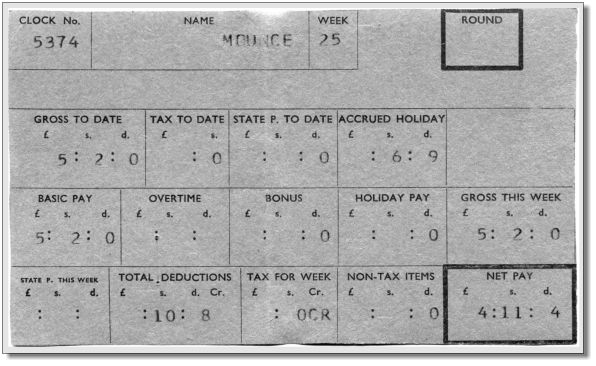

I fear my initial weekly wage as an apprentice...

... barely covered the hostel's subsidised £2-50 weekly rent, and certainly posed no immediate threat of thrusting me into the property-owning democracy so beloved, even back then, of our wise and beneficent guvmints. At the time, the average first home in the UK cost £4,000 and the average age of a first-time buyer was 25 years old. Today? The average first home costs £209,000 if you please. (Link.)

During most of 1971 I commuted daily up and down the A1 between my parents' new bungalow in Meldreth3 and Hatfield, courtesy of an amiable pair of fellow apprentices in my "year" at Hatfield Polytechnic who were being similarly sponsored, but by Marshalls in Cambridge. (They were considerably more highly-paid than I was at Hawkers.) Years three and four were spent in rented "digs" in Hatfield (complete with a delightfully old-school pensioner landlady and her World War I veteran husband) on the other side of the A1, midway between the Polytechnic, and the Hawker Siddeley "works".4

The more congenial world of UK computers

By the end of 1973 I was no longer quite such a callow youth. I'd even stopped drinking after a particularly disastrous session the day before my 21st birthday. It was a Friday, and I was the last of my "cohort" to become 21, so all my fellow students were happy to help me get well and truly hammered during this final "excuse" for celebration before facing up to the challenges of the "real" world. Recall, I was still 17 when I'd started at the Poly — not then old enough to drink legally. Worse: I was bored nearly out of my skull.

My engineering education had at least exposed me to computers. These were still fairly esoteric things, back then, of course.5 I had also picked up all the tertiary-level engineering education I felt like absorbing — fascinating and interesting though some of it was, at times. I'd managed to talk Hawkers into letting me do a one-day-a-week diploma course in computing to keep myself sane. But I had by then decided I needed to get out. I would escape the last few months of my apprenticeship, come what may. With the realisation that aero engineering and me were simply never going to fly, and rather to the amazement of my surviving student apprentices (who were all staring the pending demise of Hawkers in the face without seeming to realise what was happening in the UK to the civil aviation industry) I began looking around.

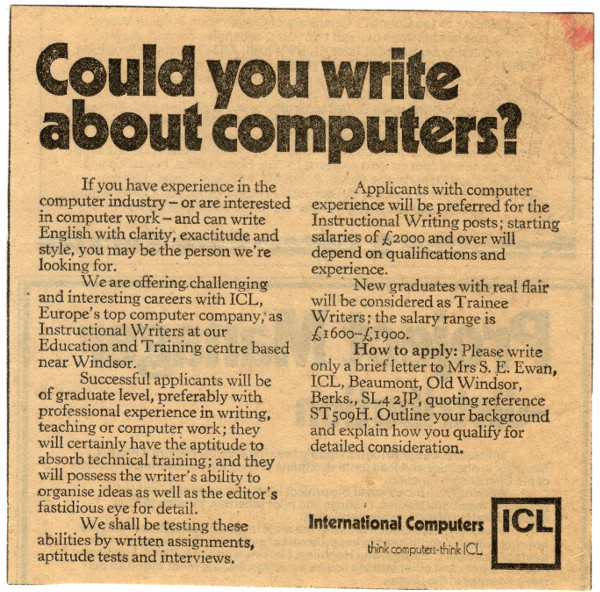

Bingo! I spotted a job ad in Dad's Torygraph that sounded much more my sort of "thing". It asked "Could you write about computers?" I didn't know the answer to that question, but I sensed it could be, erm, non-boring to find out.

I already knew I could write — apart from anything else, I was the oddball who had passed the much-dreaded and supposedly unpassable "Engineer in Society" essay paper of the CEI Part II exams. But it had simply never once occurred to me to wonder where on earth computer manuals (for example) came from, despite having devoured the dec PDP10's technical reference manual from cover to cover to get (and stay) ahead of my lecturer, who never struck me as being terribly interested in computing. (Shades of "Wilt", perhaps?)

Here's the ICL job ad I responded to, back in November 1973:

I fired off a letter. Received a writing test. Fired it back. And was immediately invited to attend a day in December of aptitude tests and interviews. About a week later I got an evening phone call at my digs from Sylvia Ewan, more or less telling me to forget the apprenticeship and please come and join ICL as a trainee, at £1,820 starting salary. Nice Xmas present! And if you're thinking "That looks like lipstick in the top corner" you're right, and there's a story to it, too.

A no-brainer. I baled happily out of the aero industry, joining ICL as a trainee instructional writer on 4th February 1974. Slap bang in the middle of the UK's "3-day working week" with all those rolling power cuts, threats of petrol rationing, and pubs and TV transmissions shutting down by 22:30 in the evenings.

Despite the undoubted romantic allure...

... of Sally, Lorna, and other lovely young ladies I met in my first couple of months at the ICL Training HQ in Beaumont, Old Windsor — they seemed to want to take me under their, erm, wings (I was very young!) — I met Christa (then working at Royal Holloway College) in the vicarage where I was renting a room that she had previously rented. She and the vicar's wife, both German, had become firm friends. Most people who met Christa became friends, I was to discover.

We promptly fell head over heels, and the rest is history. The vicar (bless him) took a dim view of having lovebirds under his roof (as it were) so we did our Registry Office "thing" and then moved together into a cheap furnished flat in Old Windsor for 17 months (at £52/month cash, no rent book) while saving enough to put down a 10% deposit on House #1, a 25-year-old solidly-built post-war three-bed semi, selling for £14,750.

We moved into that in April 1976. Then I promptly went into hospital to be parted from my rotten tonsils! Our first mortgage — initially a traditional 25-year repayment deal — was with the Abbey National. And we were very dismayed when we received our first-ever annual mortgage statement from them...

... to realise that we'd managed to repay a mere £5-70 of capital and £1,027-01 of interest! Talk about rude awakening! Hence my various forays into freelance journalism and hi-fi reviewing, followed later by numerous self-teaching training manuals6 and packages.

Pondering my latest neighbour's...

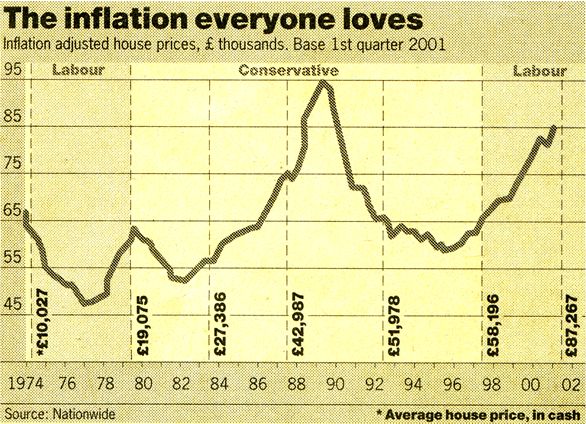

... impending relocation, and knowing that this time his house is now on the market for £389,000 or so as this yellowing clipping flutters into view...

... I recall the topic of house price inflation used to fascinate me (in the mid-1970s) a great deal more than it does nowadays. We married in September 1974, saved hard, bought our first 3-bed semi-detached house in April 1976 (for £14,650), worked hard, saved hard, bought this 4-bed detached house in July 1981 (for £41,500) when I switched jobs from ICL to IBM, worked hard, saved rather little (one income, and three mouths to feed for a decade) but managed to pay off our final mortgage exactly 25 years after starting our first one. I'd long ago sworn a mighty oath to myself that I would not have a mortgage for any longer than 25 years. My next mighty oath was when I saw that very first annual statement of capital re-paid. Hence the interest in house price inflation.

The timeline clearly demonstrates something though, in the manner of such graphics everywhere, I'd be hard pushed to say exactly what. And, of course, it cunningly omits interest rates. Meanwhile, Christa's two brothers got effortlessly richer over that same timeline as the pound slumped further and further against the German mark, inflation in the UK soared while the German economy of hard-working savers prospered, and Karl and Georg stayed in their low-rent apartments rather than stepping on to our crazy system of mortgage snakes and ladders.

We lost the Abbey habit in 1988 when the perceived wisdom changed to "get an endowment mortgage" — with the implicit subtext "and make a fortune". A year into that, my lender had changed from cheapest to most expensive in the UK (or so it felt) and a close (and overdue) reading of their small print revealed the scam for what it was. So, we wrote off the endowment, and it was off to the Royal Bank of Scotland where my IBM salary enabled us to take out a simple, no-frills, 15-year repayment mortgage with the ability to overpay as much as we wanted to clear the debt faster.

A few years later, and the Title Deeds were ours, glossing over the fact that the Royal promptly put them somewhere so safe that they only turned up in 2007 while they were looking for something else — I get that a lot these days... Abbey, meanwhile, has been swallowed up, my endowment loan provider has long since disappeared without trace, and the Royal Bank (which I now part own!) isn't exactly smelling of roses.

1981? Ah yes. The impending demise of ICL, financially gloriously mis-managed despite numerous strong technical innovations. Time for me to jump ship. Having responded to another job ad — based, I subsequently learned, on one I'd written myself just a couple of years earlier in ICL! — I trotted along to IBM Hursley, where I must have proved acceptable to them during another day of interviews and a writing test. So, into the safer haven of IBM. And, in due course, into House #2, a then-new reasonably solidly-built four-bed detached, selling for £41,500, in July 1981. Christa and Peter moved in three months later while I was on a one-week trainee writers' course in Germany (learning how to act like an "IBM Senior Associate Information Developer").

I have absolutely no idea what my house is now "worth". And I have no current intention of leaving it.

Life choices?

Computing? Yes. Christa? Yes. I definitely made both the right career and the right life choices by escaping Hatfield. (As did Big Bro, of course. Although he stayed in the aviation world, he had nonetheless emigrated to NZ in 1970, meeting his partner over there in 1971/2, just as I did a couple of years later.) And given the 25 years I went on to clock up in IBM, that worked out pretty well, too.

Je ne regrette rien. Except Christa's far too early death. That I've regretted every day since.