2014 — 29 July: Tuesday

It's a mildly sobering thought1 to be spending my first few minutes of semi-consciousness this morning answering some ancient family history questions posed by Big Bro's latest overnight email. Why? Well, it occurs to me that, if he really doesn't know the answers (and he certainly should... I was only two and a half at one of the times he asked about), I am now2 quite literally the only person on the planet who still does.

That faintly chilling...

... perspective merits a cuppa before turning to the matter of breakfast, let alone today's trial ramble. I decided yesterday that the forecast looked reasonably promising. I ask only that it be sufficiently cooler than it's been for the last week so I can re-embark on this mild exercise regime. But if I come limping home this afternoon, blistered by the heat, I shall revisit my decision. Probably by sitting with my feet in a bath of cold water while re-watching the entire GoT saga so far.

It wasn't too hot...

... and I now finally have a use for that bottle of pomegranate molasses that's been sitting on a kitchen "work" top since mid-April. Suitably diluted, and stirred, it makes an interesting flavour for a refreshing drink. I wonder where I've put my ice-cube tray.

Perfect music

If there's a better track to mask the current sound of the washing machine than "Tijuana Lady" by Gomez from their 1998 album "Bring it on", I don't know what it would be. I'm looking forward to hearing their live set from 2002 that was on Gideon Coe's show last week.

Talk about...

... stating the bl****ng obvious:

But considering the inability of Congress to reach consensus over relatively straightforward public policies (such as raising the debt ceiling to meet the nation's financial obligations or funding for transportation infrastructure projects already underway), it's unlikely we'll see the repeal of pot prohibition anytime soon.

I still recall reading ads calling, in a perfectly well-reasoned manner, for this change over 40 years ago in the American magazines I was reading at the time. You have to admire (and laugh at) a continuing display of such staggering hypocrisy on such a large scale. Not that the UK is exactly a beacon of shining virtue.

Of course, Jenji ("Weeds") Kohan may yet be proved correct :-)

I am stepping off...

... the upgrade treadmill. Although I use, and have been using since 1991 or so, ever more sophisticated versions of what began life on the Acorn Risc OS platform as "Artworks" from Computer Concepts, the German software house that now owns them has been steadily charging more and more for increasingly less incremental function, year by year. I decline to pay yet another £79 this year (my special offer discount price) to step up from Designer Pro X9 to X10 just to gain some pretty, but pretty minor, colour handling and editing features. None of which I have any need for.

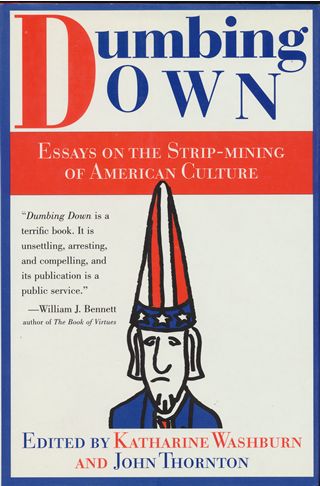

I have a book...

... (actually I have several, but let that pass) to which I return on occasion for a refreshing dip. Here's a typical extract, from an essay in it called "Last Night at the Planetarium" by Ken Kalfus:

The public's retreat from participation in science has never been starker. If once we could see the stars from our backyards, possibly gazing through a cheap telescope, now the universe is something to be observed on television. Our science fiction series have prepared us for this. Note that on the bridge of the Enterprise there are no windows. Comfortably settled in a souped-up La-Z-Boy, Captain Kirk watches the stars rush by on a large-screen TV. The very popular film image of stars rushing by a spaceship in flight, or even swimming by in a leisurely fashion, obscures basic knowledge about the universe we live in: its size, the distances between stars, and the flat-out impossibility of closing the distances between them by traveling faster than light. Despite rhetorical allusions to the vastness of our universe, our popular culture shies away from accepting these constraints in its fictions because they're too scary: to comprehend the size of the universe is to comprehend our isolation within it.

If religion employs faith and the occult employs mysticism, then the favorite tool of science fiction is wishful thinking, particularly the wishful thought that we might someday travel faster than light. While wishful thinking makes for good space opera, should it be a factor in public science policy? Here before me is a recent space-travel-boosting issue of the popular science magazine Discover (published by a subsidiary of the people who urge us to wish upon a star, the Walt Disney Company). In it, NASA administrator Daniel Goldin proposes establishing a lunar observatory, free of atmospheric distortion, to search for Earth-like planets outside our solar system. He suggests that the discovery of such planets "might inspire us to invent warp drive." In fact, it would take more than inspiration to invent a faster-than-light "warp drive"; it would take a refutation of our understanding of the laws of physics. To talk of such a refutation, based on neither observation nor reason, is to degrade the means by which this understanding has been accomplished. When it's done by the chief of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, it denigrates the entire scientific enterprise.

My emphasis. I observe no improvement in the representation of science within Hollywood's outpourings since its publication. That essay (or, at least, an Op Ed piece in the NYT along the same lines) was actually the catalyst for the whole book:

I must admit, I wonder how Daniel Goldin got his job.